WND October 31, 2017

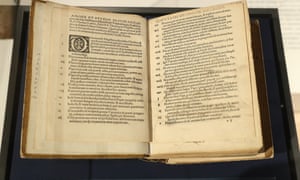

On Oct. 31, 1517, an Augustinian monk named Martin Luther posted 95

debate questions on the door of Wittenberg Church, which began the

movement known as “the Reformation.”

In 1521, 34-year-old Martin Luther was summoned to stand trial before

the most powerful man in the world, 21-year-old Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V. Charles V of Spain’s empire spanned nearly two million square

miles across Europe, the Netherlands, the Far East, North and South

America and the Caribbean.

The Philippine Islands were named after his son, King Philip II of Spain. The sun never set on the Spanish Empire.

At the Diet of Worms, Charles V initially dismissed Luther’s theses

as “an argument between monks” and simply declared Martin Luther an

outlaw. Martin Luther was hid by Frederick of Saxony in the Wartburg

Castle, where he translated the New Testament into German. Charles V’s

unruly troops sacked Rome and imprisoned Pope Clement VII for six

months.

Charles V oversaw the Spanish colonization of the Americas, and began

the Counter-Reformation. He eventually responded to the pleadings of

the priest Bartolomé de Las Casas and outlawed the enslavement of native

Americans.

Gold from the New World was used by Spain to push back the Muslim

Ottoman Empire’s invasion of Europe. Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent’s

Ottoman fleet dominated the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea and the

Persian Gulf. Suleiman conquered into Christian Hungary, Christian

Serbia and Christian Austria, in addition to controlling the Middle East

and North Africa. In 1529, 35-year-old Suleiman the Magnificent sent

100,000 Muslim Turks to surround Vienna, Austria.

Martin Luther wrote: “The Turk is the rod of the wrath of the Lord

our God. … If the Turk’s god, the devil, is not beaten first, there is

reason to fear that the Turk will not be so easy to beat. … Christian

weapons and power must do it. …”

Martin Luther continued: “(The fight against the Turks) must begin

with repentance, and we must reform our lives, or we shall fight in

vain. (The Church should) drive men to repentance by showing our great

and numberless sins and our ingratitude, by which we have earned God’s

wrath and disfavor, so that He justly gives us into the hands of the

devil and the Turk.”

In an attempt to unite the Holy Roman Empire against the Ottoman

Muslims, Charles V agreed to a truce recognizing the Protestants, as

Eric W. Gritisch wrote in “Martin – God’s Court Jester: Luther in

Retrospect” (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983, p. 69-70): “Afraid of losing

the much-needed support of the German princes for the struggle against

the Turkish threat from the south, Emperor Charles V agreed to a truce

between Protestant and Catholic territories in Nuremberg in 1532. … Thus

the Lutheran movement was, for the first time, officially tolerated and

could enjoy a place in the political sun of the Holy Roman Empire.”

As the Islamic threat intensified, reformer John Calvin wrote to

Philip Melanthon in 154 (“Selected Works of John Calvin: Tracts &

Letters,” I: 373): “I hear of the sad condition of your Germany! … The

Turk again prepares to wage war with a larger force. Who will stand up

to oppose his marching throughout the length and breadth of the land, at

his mere will and pleasure?”

Followers of the reformers who “protested” certain doctrines, were

generally referred to as “Protestants.” Some Protestants refused to help

Charles V who was defending Europe from the Muslim invasion. Finally,

Charles V made a treaty with the German Lutheran Princes by signing the

Peace of Augsburg, September 25, 1555, ceasing the religious struggle

between Lutherans and Catholics.

A line in the treaty, “cuius regio, eius religio,” allowed each king to decide what was to be believed in his kingdom.

A month later, Oct. 25, 1555, suffering from severe gout, Charles V

abdicated his throne and lived the rest of his life secluded in the

monastery of Yuste, leaving his son Philip II to rule.

As different kings in Europe chose different denominations for their

kingdoms, millions migrated from one country to another simply for

conscience sake. Many of these Christian religious refugees fled Europe

to settle colonies in America.

New York University Professor Emeritus Patricia Bonomi, in her

article “The Middle Colonies as the Birthplace of American Religious

Pluralism” wrote: “The colonists were about 98 percent Protestant.”

Of the 56 signers of the Declaration, most were Protestant, with the notable exception of Catholic Charles Carroll of Maryland.

British Statesman Edmund Burke addressed Parliament, 1775: “All

Protestantism … is a sort of dissent. But the religion most prevalent in

our Northern Colonies is a refinement on the principle of resistance;

it is the dissidence of dissent, and the protestantism of the Protestant

religion.”

Samuel Adams stated when he signed the Declaration of Independence:

“This day, I trust, the reign of political protestantism will commence.”

Martin Luther, who died in 1546, wrote: “I am much afraid that

schools will prove to be the great gates of hell unless they diligently

labor in explaining the Holy Scriptures, engraving them in the hearts of

youth.”