Washington Times December 31, 2019

For more than 500 years, the most popular and influential book after

the Bible was “The Golden Legend” by Jacobus de Varagine. At the end of

the 13th century, Varagine was grappling with how medieval Christians

perceived time: He mapped the liturgical calendar and the stories of

feast-day saints associated with it. The book was a bestseller.

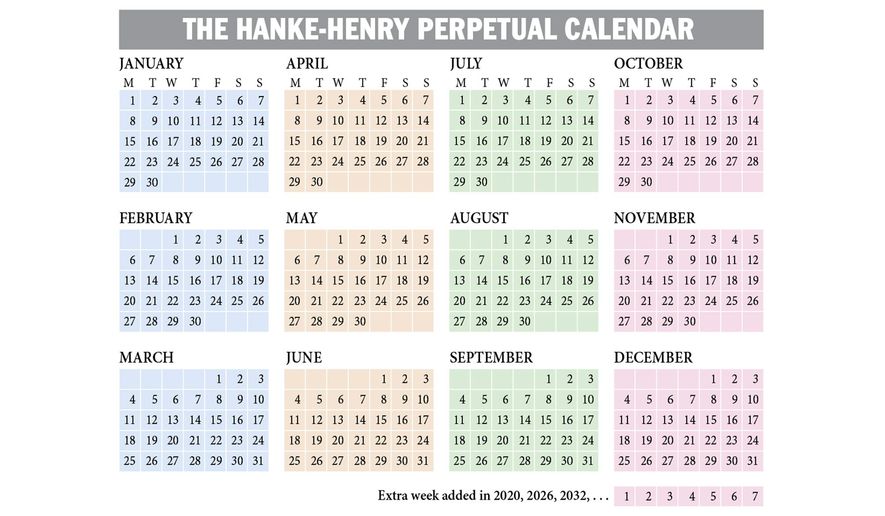

Flash forward to today. We now waste a great

deal of time fumbling around with the flawed Gregorian calendar. For one

thing, new calendars have to be printed ever year. What a waste of both

time and money.

But this isn’t the only cost dished up by our

Gregorian calendar. Indeed, there are a number of problems and

inefficiencies associated with it. Under the Gregorian calendar, the

scheduling of the days for holidays, sporting events and school

schedules — to name but a few — must be redone each year. What a waste

of time and money.

The Gregorian calendar also causes confusion when it comes to the

age-old idea of “time is money.” For example, to determine how much

interest accrues for a wide variety of instruments — bonds, mortgages,

swaps, forward rate agreements, etc. — day counts are required. The

current calendar contains complexities and anomalies that create

day-count problems.

And there are other financial problems

generated by the Gregorian calendar. For example, back in 2013, Apple

was caught up in a quarterly reporting fiasco. Following its

firt-quarter 2013 earnings announcement, Apple suffered its worst

one-day loss in four years as a result of the company’s failure to meet

Wall Street’s expectations. This was largely due to a simple

calendar-generated error — most analysts failed to account for the fact

that Apple’s Q1 2013 was one week shorter than the same quarter the year

before.

The past 400 years have only seen a handful of cohesive efforts to

standardize the modern calendar or iron out the kinks of the Gregorian

calendar. The crusade for calendar modernization found one of its most

prominent champions in 19th-century industrialist George Eastman, the

founder of the Eastman Kodak Co. Driven by a desire to create a more

business-friendly calendar, he developed the “Eastman plan.” It was one

of the first cogent models of a fixed (or permanent) calendar and was

designed to eliminate the practical and financial inefficiencies

generated by the Gregorian calendar system.

However innovative, the Eastman plan was in

many respects crude, failing most crucially to account for and preserve

the Sabbath. Like many past attempts at calendar reform, the Eastman

plan was doomed by its failure to address religious and cultural

concerns. Indeed, one of the major criticisms of such calendar reforms

is that they interfered with religious days of rest, which play an

integral role in the organization of economic activity, i.e. “the work

week.”

No comments:

Post a Comment